The Pyramids at the Giza Plateau

Table of Contents

The Giza Plateau is home to the three most famous pyramids in the world and stands as the most important archaeological complex of ancient Egypt. Located on the western outskirts of Cairo, Egypt, it was one of the necropolises of Memphis, the capital of the Ancient Egyptian Kingdom. About 8 km from the ancient city of Giza, on the Nile, and 25 km southwest from the center of Cairo, the plateau includes the Pyramid of Cheops (or Great Pyramid), the Pyramid of Chefren, the Pyramid of Menkaure, and the Sphinx, surrounded by other small structures known as the Pyramids of the Queens, funerary temples, processional ramps, downstream temples, and cemeteries from various eras.

The Great Pyramid of Giza: An Antediluvian Wonder

The Pyramid of Cheops, also known as the Great Pyramid of Giza or the Pyramid of Khufu, is the oldest and largest of the three main pyramids on the Giza Plateau. This ancient marvel is the only one of the seven wonders of the ancient world still standing today. Constructed with over 2.3 million blocks weighing between 2.5 and 70 tons, it is believed to have been built over a period of 15 to 30 years. Egyptologists estimate that an average of one block was placed every 3 minutes, day and night, for over 20 years.

Preparation of the Site

Before construction began, the ground was carefully leveled to provide a stable foundation for the immense structure. This involved the removal of loose debris and the flattening of the bedrock. Evidence suggests that the ancient builders used a combination of water and measuring tools to achieve this remarkable level of precision. They likely created channels and flooded the area, using the water level as a guide to ensure a perfectly flat surface. The meticulous preparation of the site underscores the advanced engineering skills of the ancient Egyptians.

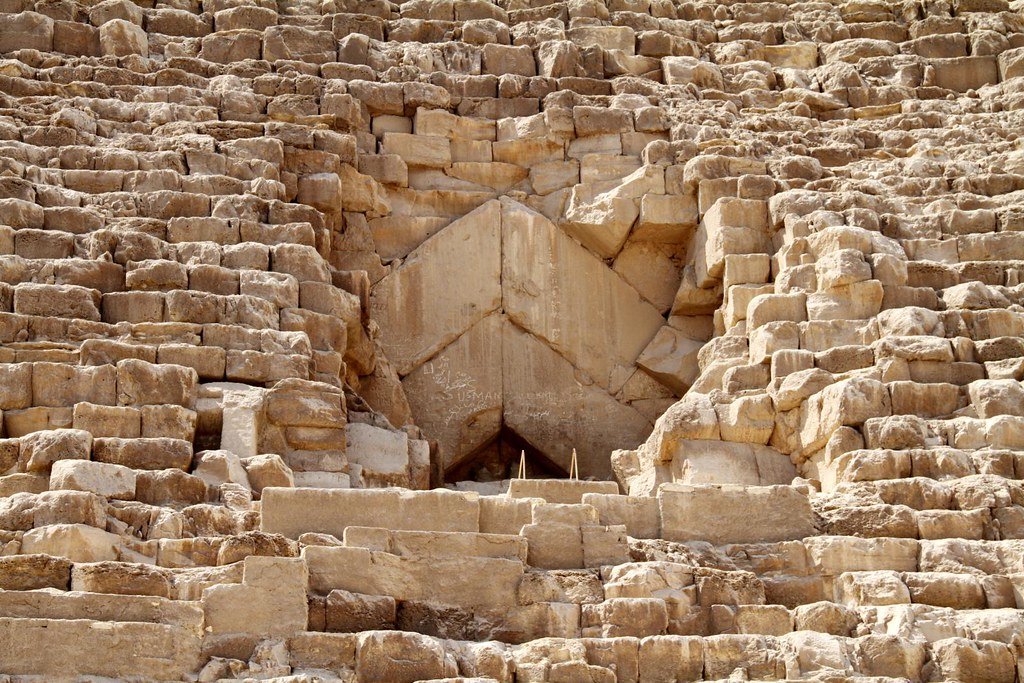

Although modern Egyptologists believe that the pyramid was built as the tomb of Pharaoh Khufu, no mummies or hieroglyphic inscriptions have been found inside any of the pyramids at the Giza Plateau. The Egyptians typically adorned funerary structures with extensive hieroglyphs, making the lack of such decorations in the Great Pyramid particularly enigmatic. The original entrance features huge slant megaliths covered by additional blocks, suggesting that the original structure may have been different.

Enigmatic Features

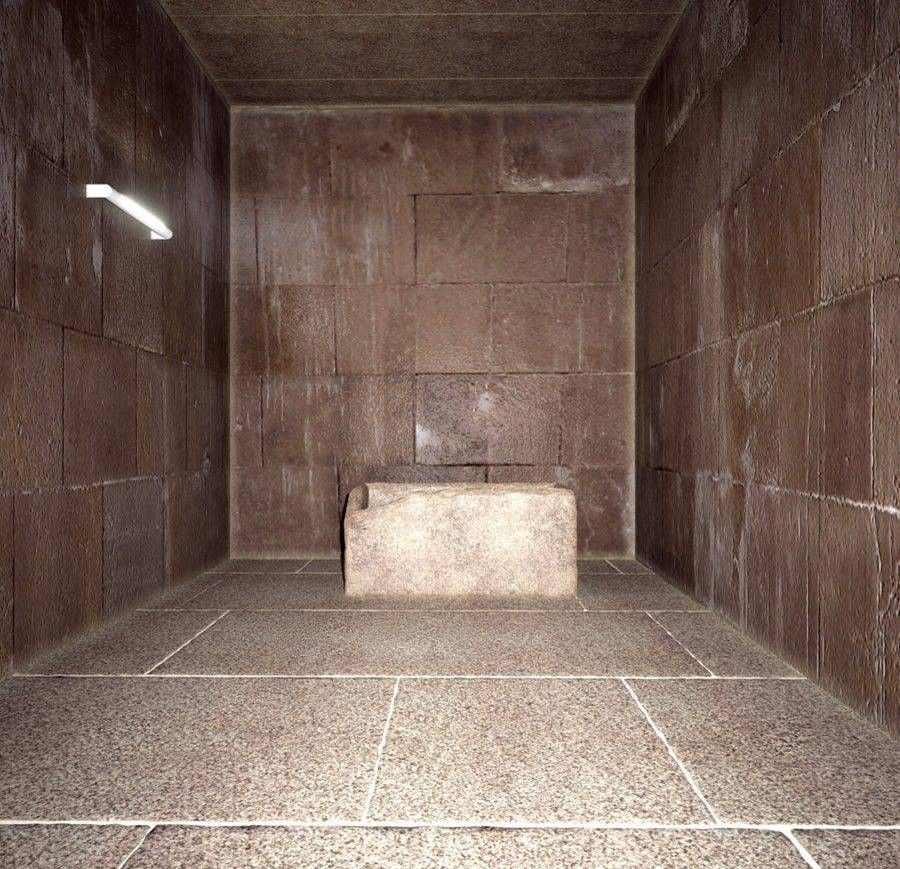

The Great Pyramid’s foundation blocks and upper blocks display significant differences, leading some to speculate that a pre-existing structure was built upon. The King’s Chamber, made of large granite blocks from the Aswan quarries, is an architectural marvel with a ceiling composed of nine stone blocks totaling 400 tons. These blocks are so precisely cut and placed that a sheet of paper cannot fit between them.

The only object found in the King’s Chamber is a roughly hewn pink granite sarcophagus, which is wider than the passage to the chamber, indicating it was placed before the ceiling was completed. Unlike other sarcophagi found in Egypt, which are typically well-finished and decorated, this one is quite plain, suggesting it may have been considered historical even by the pyramid’s builders.

Inside The Great Pyramid Of Giza

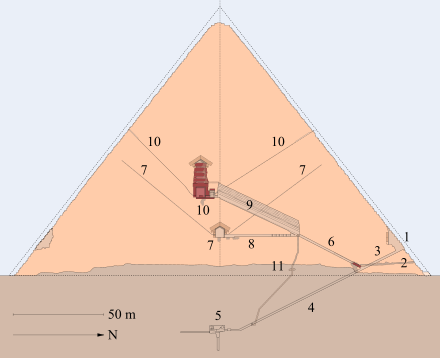

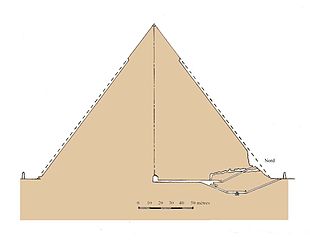

Schematic section of the Great Pyramid:

Schematic section of the Great Pyramid:

- original entrance

- new entry

- descending passage

- descending tunnel

- lower chamber

- ascending tunnel

- intermediate

- chamber

- horizontal tunnel

- great gallery

- upper chamber

- vertical tunnel

The King’s Chamber

The King’s Chamber: An Architectural Marvel

The King’s Chamber, located within the Great Pyramid of Giza, is a remarkable example of ancient Egyptian engineering and craftsmanship. This chamber, often associated with the Pharaoh Khufu, who commissioned the pyramid, exhibits several unique features that continue to intrigue researchers and historians.

Dimensions and Structure

The King’s Chamber measures 10.47 meters in length, 5.234 meters in width, and 5.974 meters in height. Its structure is reminiscent of the Djed, an ancient Egyptian symbol representing stability. The precise dimensions of the floor, measuring exactly 10 by 20 cubits, suggest that the ancient Egyptians used a unit of measurement equivalent to 0.524 meters, slightly different from the generally accepted 0.525 meters.

Construction Materials and Precision

The walls, floor, and ceiling of the chamber are constructed from large granite blocks sourced from the Aswan quarries, located some 800 kilometers south of Giza. The transportation and placement of these blocks underscore the incredible logistical capabilities of the pyramid builders. The blocks are cut and fitted with such precision that it is impossible to insert a sheet of paper between them, a testament to the advanced techniques used by the ancient Egyptians.

The ceiling of the King’s Chamber is particularly noteworthy. It is flat and composed of nine massive stone blocks with a combined weight of approximately 400 tons. This remarkable engineering feat not only highlights the Egyptians’ architectural prowess but also their ability to handle and position such enormous stones with accuracy.

The Sarcophagus

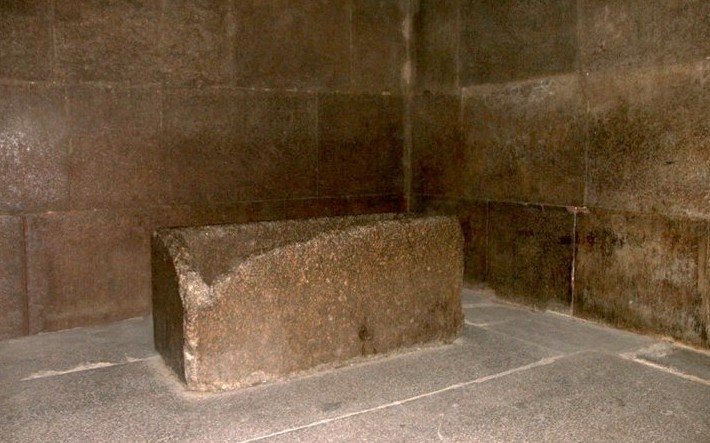

The only object within the King’s Chamber is a rectangular monolithic sarcophagus made of pink granite. This sarcophagus has a broken corner and lacks a lid. Interestingly, it is slightly wider than the passageway leading to the chamber, indicating that it must have been placed before the ceiling was completed. This fact points to careful planning and sequencing in the construction process.

Contrary to the finely finished walls of the chamber, the sarcophagus appears roughly hewn, with visible traces of cutting and excavation tools. This rough finish contrasts sharply with the well-finished and decorated sarcophagi found in other pyramids of the same period. The disparity has led to various theories about its origin and purpose.

Theories Regarding the Sarcophagus

British Egyptologist Sir William Flinders Petrie suggested that a more elaborately decorated sarcophagus was initially planned but was lost in transit on the Nile north of Aswan. According to this theory, the roughly finished sarcophagus was a hastily arranged replacement. However, this explanation does not account for why the second sarcophagus was not completed in situ, a process that would have been feasible given the advanced stone-working skills of the Egyptians.

An alternative theory posits that the sarcophagus was placed in the chamber in its current unfinished state because it was already considered an historical artifact by the pyramid’s builders. This theory suggests that the sarcophagus was preserved intact as a significant relic, potentially already ancient by the time it was placed in the pyramid. This would align with the observation that the sarcophagus differs significantly from others found throughout Egypt, which are typically larger, intricately decorated, and often nested one inside another, with the inner mummy carefully preserved.

A Lasting Enigma

The King’s Chamber continues to be a focal point for research and speculation. Its precise construction, the massive granite blocks, and the enigmatic sarcophagus all contribute to the ongoing mystery surrounding the Great Pyramid. These features, combined with the chamber’s potential symbolic significance, ensure that it remains an enduring subject of fascination and study in the field of Egyptology.

The Shafts

The ventilation ducts in the upper chamber were described as early as 1610, while the ducts in the middle chamber were not discovered until 1872.

In that year, Waynman Dixon, a Scottish railway engineer, and his friend, Dr. James Grant, noticed a crack in the south wall of the Queen’s Chamber. After shoving a long thread into the gap, indicating that there was probably a void behind the slab, Dixon hired a carpenter named Bill Grundy to cut the slab of the wall.

A rectangular channel was thus discovered, on average 20.5 cm wide and 21.5 cm high, which winds for almost 3 meters inside the pyramid, before curving upwards at an angle of about 39 °.

Since the upper chamber had two similar tunnels, Dixon measured the location, analogous to the newly discovered tunnel, on the north wall and, as expected, Grundy found the opening of the twin tunnel.

Inside the north tunnel, three artifacts were discovered: a small bronze hook, a wooden rod (described as similar to cedarwood) 12 cm long, and a sphere of black diorite with bronze inserts.

These objects remained in the hands of the Dixon family until the 1970s, when they were donated to the British Museum where they are still kept and, since the 1990s, exhibited.

In December 2020 the relic in cedarwood at the University of Aberdeen was radiocarbon dated, detecting a dating back exactly (+/- 200 years statistical error) to 3341 BC; based on these data it was hypothesized a possible construction of the pyramid at least 500 years earlier.

The adventurers also lit fires to channel the smoke into the vents in an attempt to find out where these led. The smoke stagnated in the north vent but disappeared in the south vent and was not seen exiting the outside of the pyramid.

The openings of both conduits are located at approximately the same level in the chamber, at the top junction of the first granite slab. The northern opening is slightly lower, while the plane of the southern opening is approximately at the height of the junction.

The ducts in the Queen’s Chamber were explored in 1993 by the German engineer Rudolf Gantenbrink, under the supervision of archaeologist Rainer Stadelmann of the Deutsches Archäologisches Institut, using a crawler robot of his own design called Upuaut 2. Exploring the south duct, at the end of an ascent of 65 m, he discovered a limestone slab with two eroded copper handles inserted, closing the tunnel.

Gantenbrink also tried to explore the north shaft, but it was decided not to continue beyond a bend 18 m from the entrance, because it could have caught the robot.

In 2002, the National Geographic Society created a similar robot, called the Pyramid Rover, which made a hole in the central area of the south conduit slab, only to discover, on Sept. 17, another slab of stone behind it, but devoid of any handles.

The following day the north duct was finally explored, where a completely similar closing slab was discovered.

The research continued in 2009 with the Djedi project, which adopted a camera able to orient itself freely within the duct (micro snake camera), was able to penetrate the first hatch of the southern duct through the hole in 2002, and view all sides of the small compartment behind it. Signs written in red paint were discovered, possibly hieroglyphs.

The camera also framed the copper handles built into the hatch inside the small compartment. The inside of the hatch had been refinished, which suggests it wasn’t just in place to prevent debris from getting into the duct.

The Great Gallery

The Great Gallery (9) constitutes the continuation of the Ascending Tunnel but is 8.6 meters high and 46.68 meters long. At the base, it is 2.06 meters wide, but after 2.29 meters the stone blocks fall inwards by 7.6 cm on each side. There are 7 of these steps so that at the top the tunnel is only 1.04 meters wide.

The roof is made of blocks placed at a slightly more inclined angle with respect to the floor, so as to fit each block into a recess made in the top of the tunnel-like a jack tooth. The aim is to have each block supported by the tunnel wall rather than resting on the block below it, which would have resulted in excessive cumulative pressure at the end of the tunnel.

The floor of the Grand Gallery consists of a double staircase arranged on each side, 51 cm wide, which leaves in the center space for a smooth 1.04-meter wide ramp. Near the floor, there are various niches of unknown use.

The lower end of the tunnel is an important crossroads, as, in addition to being the point where the ascending tunnel leads into the Great Gallery, on the right, there is a hole in the wall (now blocked by a metal mesh) which constitutes the upper outlet of the Vertical tunnel (12). From here also starts the horizontal tunnel (8) leading to the so-called Queen’s Chamber (7).

At the upper end of the tunnel, on the right side, there is a hole in the ceiling that opens into a short tunnel through which you can access the lower discharge chamber.

As usual, when it comes to archaeological theories regarding these structures, the purpose of the Grand Gallery has not been clearly determined.

There are speculations regarding the Great Pyramid of Giza containing more shafts and chambers that are yet to be discovered.

The Pyramid Of Chefren

The Chefren pyramid is the second largest pyramid of the Giza Plateau after the Great Pyramid. In the lower half, it has large rough and irregular blocks arranged with poor precision, while towards the top these appear more uniformly arranged. Over the millennia, various seismic movements have caused the stones to move by a few millimeters.

The pyramid appears higher than that of Cheops because it was built on a rock base about 10 meters high. Its height would appear even greater if it were not without part of the top and the pyramidion.

It has the particularity of being the only pyramid that preserves on the top a part of the white Tura limestone roof that originally covered the entire structure. The base is covered with “variegated Ethiopian stone” (as defined by Herodotus) or red and gray granite from Aswan.

It has two entrances, one at about 11.54 meters high, the other at ground level, which is the one currently used for visits.

Walking inside the entrance, there’s a descending gallery about 32 meters long which leads to a horizontal corridor ending into a chamber.

Egyptologists maintain this was the unfinished burial chamber of the pharaoh. However, a more logical hypothesis maintains this was never meant to be a burial chamber. Imagine building such a structure and then leaving the most important part of it unfinished.

This one measures 14.15 meters by five, it is unique, carved out of stone, with a gabled ceiling formed by 17 pairs of limestone beams and located below the level of the courtyard.

The only funerary furniture found in the red granite sarcophagus buried “at ground level”, completely devoid of inscriptions and broken, similar to the one found inside the Great Pyramid.

From the chamber, an uphill gallery leads to two apartments with a horizontal corridor connected to the first.

There is also another large room which purpose is still disputed today.

The Pyramid Of Menkaure

The Pyramid of Menkaure is the smallest among the pyramids of the Giza Plateau. Built about 450 meters southwest of the Chefren pyramid, the project went through several stages, and various materials and techniques were used.

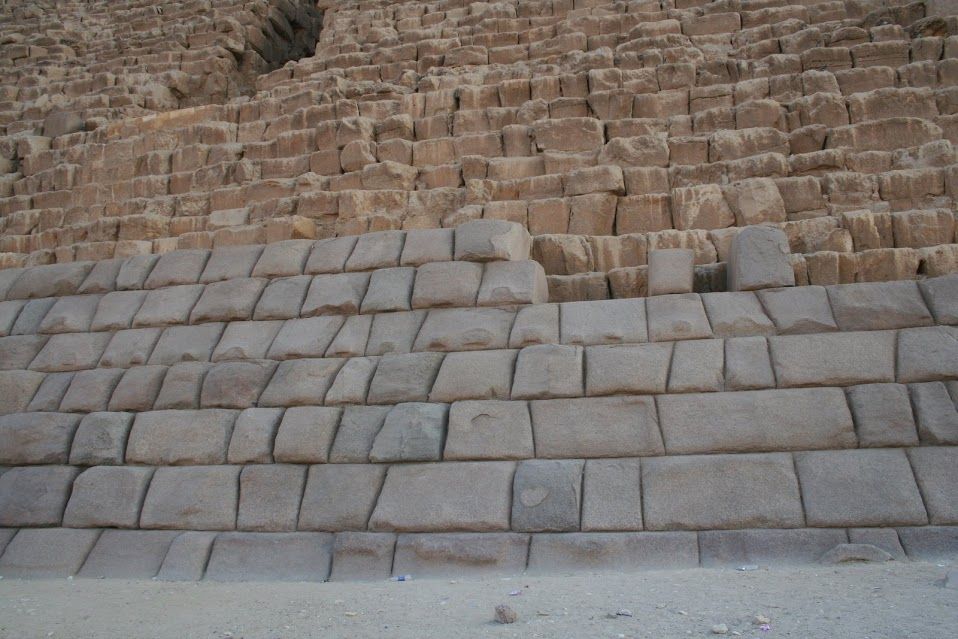

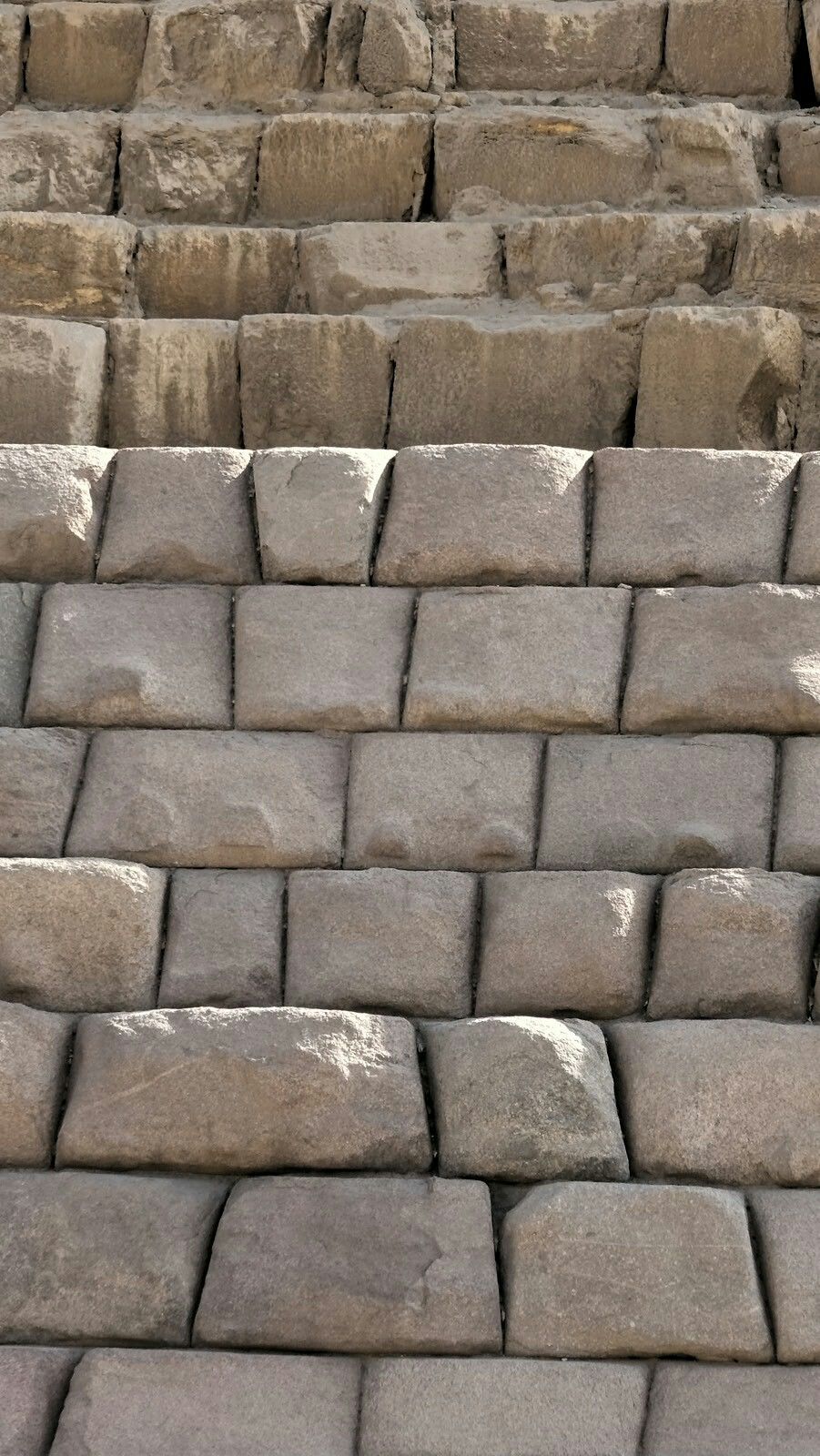

This may suggest that the Egyptians built over and modified a pre-existing structure

Its volume does not exceed 250,000 m³, which is a tenth of that of Cheops, but the megalithic blocks used are much larger even than the ones used for the pyramid of Chefren.

Originally, the pyramid should have been completely covered with the spectacular red granite of Aswan.

The north side retains part of the coating, which, however, is not smooth towards the top, thus giving the impression of unfinished work.

There is also a large breach, due to Saladin’s son, al-Malik al-ʿAzīz ʿUthmān b. Yūsuf, opened it in 1196 to break into the pyramid.

The interior of the pyramid is very complex, has an entrance to the north at about 4 meters high and a descending gallery covered in pink granite of about 32 meters and with an inclination of 26 ° that leads to a vestibule decorated with bas-reliefs with the “palace facade” motif and a subsequent large corridor about 13 meters long, 4 meters wide and 4 meters high.

This corridor opens into the alleged burial chamber located 6 meters below the ground level which has a pit in the floor, from which a closed corridor extends.

The richness of the pyramid is given by the massive presence of granite from distant quarries in Upper Egypt, a very hard stone that is extremely difficult to work with.

The granite was removed as early as 500 AD. and in 1827 the pasha Muhammad Ali used it for the construction of the arsenal of Alexandria.

A feature noted by scholars is that the marks left on the walls by the tools of the Egyptian workers indicate with certainty that the first lower corridor was excavated from the inside out while the second, the upper one exactly from the outside inwards.

By observing the so-called casing stones from the Pyramid of Menkaure around the base of the Pyramid we can find the same workmanship and precision of the Osireion.

As a matter of fact, even though Zahi Hawass is a famous mainstream Egyptologist that goes against alternative theories, he himself believes that the Osireion may have three underground shafts that connect the temple to the pyramids at the Giza Plateau and to the Sphinx along with the Valley Temple.

Flinders Petrie, a famous English Egyptologist as well as one of the first real researchers of the pyramids and the Giza Plateau, related the precision of the casing stones as to being “equal to opticians’ work of the present day, but on a scale of acres” and said that “to place such stones in exact contact would be careful work, but to do so without cement in the joints seems almost impossible”.

Water Transport Theory

Recently, some researchers have proposed that a now-vanished stream of water near the pyramids might have been used to transport the massive stone blocks on papyrus boats. This theory, however, faces significant challenges. The logistics of moving such enormous blocks via water, especially on lightweight papyrus boats, seems highly impractical. The blocks, some weighing up to 70 tons, would have required incredibly sturdy and stable vessels, far beyond what papyrus boats could realistically handle. Moreover, the precise and careful placement of these massive stones in constructing the pyramids further complicates the plausibility of this theory.

Theories and Speculations

Modern theories suggest that rather than using slave labor, the pyramids were built by skilled laborers who were honored for their work. The precision and scale of the pyramids’ construction continue to fuel speculation about ancient advanced technologies now lost to history. The differences in construction techniques between the foundation and upper blocks, the enigmatic shafts, and the lack of typical burial artifacts suggest the pyramids might have served purposes beyond royal tombs.

The Merer Papyrus

The Merer papyrus, discovered relatively recently, may describe the transportation process of the blocks used in the pyramid’s construction. However, this document only details the transportation of a small portion of the stones, suggesting it might refer to renovations rather than the original construction.

A Lasting Legacy

The Giza Plateau remains a source of fascination and mystery, capturing the imagination of scholars and enthusiasts alike. The Great Pyramid, in particular, stands as a testament to ancient ingenuity and possibly to an era predating known Egyptian civilization. Its precise construction, vast scale, and mysterious origins ensure that the pyramids continue to be a focal point for both academic research and popular speculation, inviting endless exploration and wonder about their true origins and purposes.