The Megalithic Churches Of Lalibela

Lalibela is a city in northern Ethiopia famous for its megalithic churches carved directly into the rock.

It is one of the holiest cities in Ethiopia, second only to Axum, and a pilgrimage center. Unlike Axum, the population of Lalibela is almost completely Ethiopian Orthodox Christian.

Ethiopia was one of the first nations to adopt Christianity in the first half of the 4th century, and its historical roots go back to the time of the Apostles.

The Rock-Hewn Churches were declared a World Heritage site in 1978.

The megalithic churches of Lalibela are attributed to the emperor Gebre Mesqel Lalibela (1162-1221), although recent scholarship has suggested origins as early as the late Aksumite period.

However, there are no officially confirmed hypotheses regarding their construction.

Details about the construction of the 11 megalithic churches at Lalibela have in fact allegedly been lost, making the enigma even stranger.

The later Gadla Lalibela, a hagiography of the king, states that he carved these churches out of stone with the only help of angels.

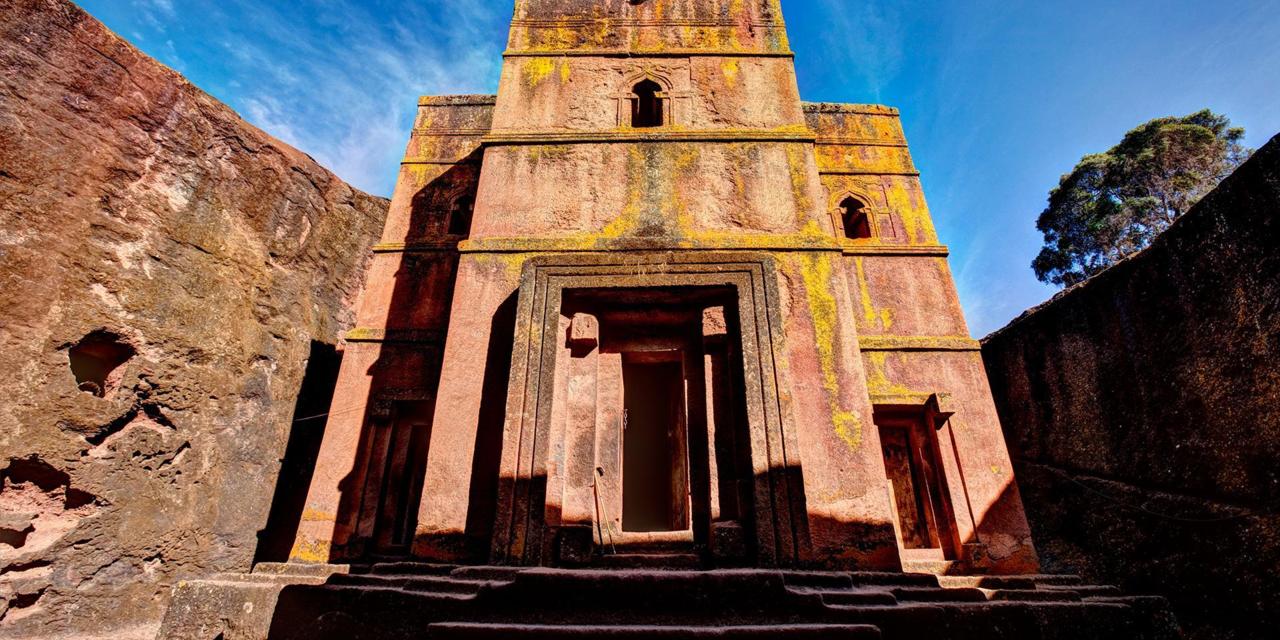

They were all carved directly into single blocks of stone.

According to the narrative of the Portuguese embassy to Ethiopia in 1520/1526, written down by Father Francisco Álvares and published in 1540, the Lalibelian priests claimed that the churches took 24 years to construct and that they were made by unknown white men under the orders of King Lalibela.

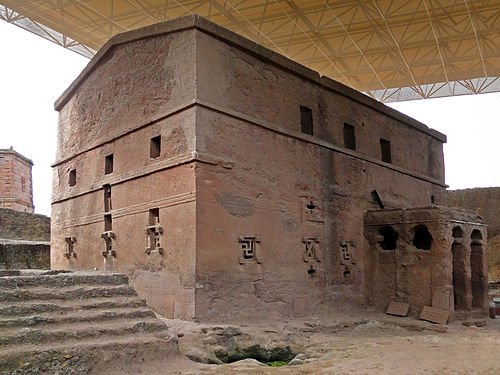

They can’t be dated to an exact period, and some showcase symbols from cultures that thrived in the very distant past, like the swastika, a sacred symbol of the East as well as many other ancient civilizations throughout the world.

The Unesco site includes 11 churches organized into four groups:

The northern group includes:

- the Biete Medhane Alem (House of the Savior of the World), the seat of the Lalibela Cross, and believed to be the largest monolithic church in the world, probably a copy of Our Lady of Zion in Axum

- the Biete Maryam (House of Miriam / House of Mary), perhaps the oldest of the churches, and a replica of the Tombs of Adam and Christ

- the Biete Golgotha Mikael (House of Golgotha Mikael), known for its murals and said to contain the tomb of King Lalibela)

- the Biete Maskal (House of the Cross)

- the Biete Denagel (House of the Virgins).

The wester group includes:

- Bet Giorgis (Church of San Giorgio), considered the most finely executed and best-preserved church.

The eastern group, which includes:

- Bet Amanuel (House of Emmanuel), possibly the former royal chapel

- the Biete Qeddus Mercoreus (House of S. Mercoreos / House of San Marco), which may be a former prison

- the Biete Abba Libanos (House of the abuna Libanos)

- the Biete Gabriel-Rufael (House of the angels Gabriel and Raphael), perhaps an ancient royal palace, connected to a sacred bakery

- The Biete Lehem (Hebrew Bethlehem: בֵּית לֶחֶם, House of the Sacred Bread).

The Datation Problem

There is some controversy regarding the date of construction of the churches.

David Buxton established the generally accepted chronology in 1970, pointing out that “two of them follow with great fidelity of detail the tradition represented by Debre Damo and Yemrahana Kristos”.

Since it must have taken longer than the few decades of King Lalibela’s reign to carve these structures in living rock, Buxton assumes that the work lasted until the 14th century.

However, David Phillipson, professor of African archeology at Cambridge University, has proposed that the churches of Merkorios, Gabriel-Rufael, and Denagel were initially carved out of the rock half a millennium earlier, as fortifications or other palatial structures in the latter days of the Axumite kingdom, and that Lalibela’s name was simply associated with such structures after her death.

Buxton acknowledges the existence of a tradition that “the Abyssinians asked for the help of foreigners” to build their monolithic churches and researchers such as Graham Hancock maintain they were built with the aid of the Templar Knights, which would justify the popular accounts about “white men” helping the king build the structures.